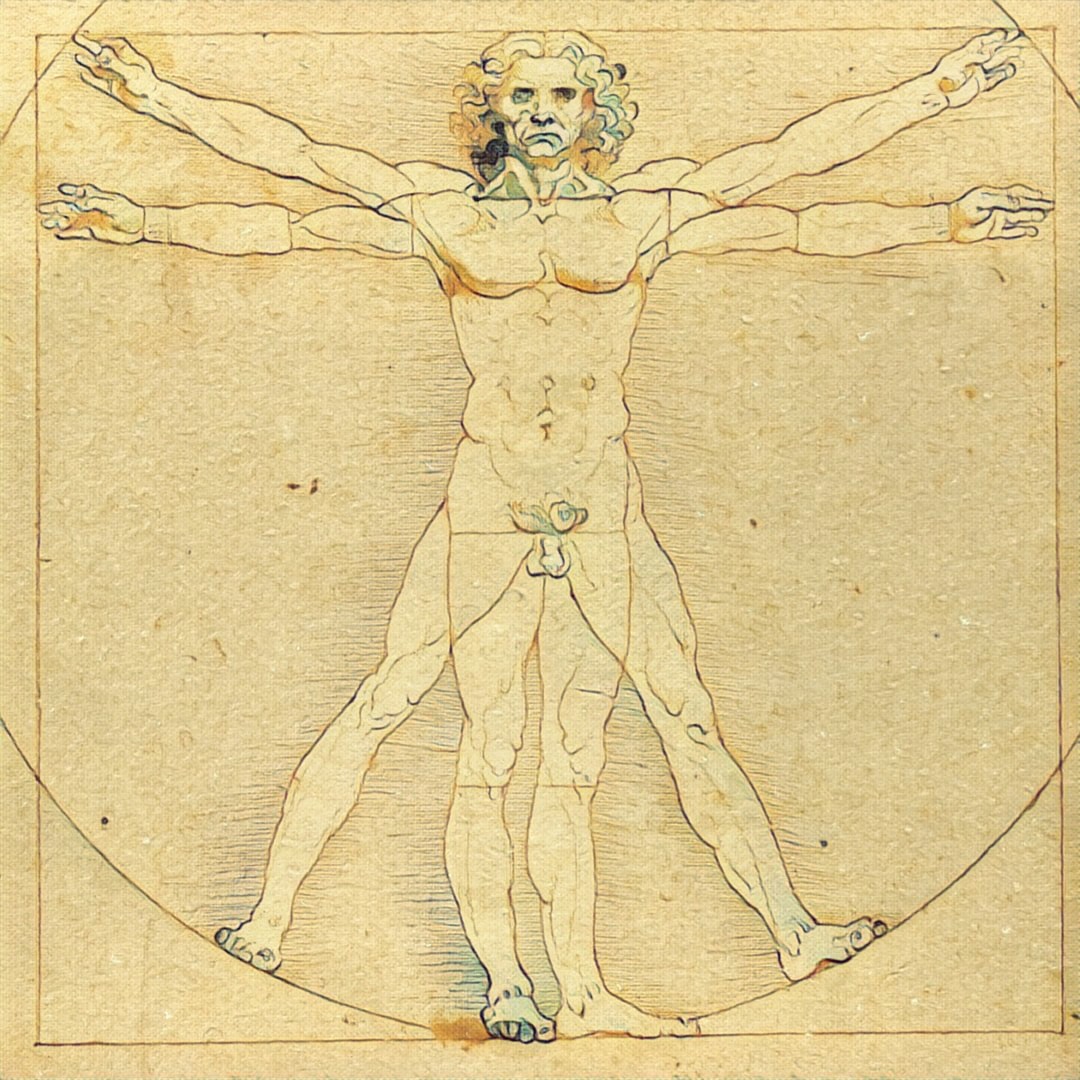

Develop A Complete Mind

“Study the science of art; study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.” ― Leonardo da Vinci

The value of art and science on its own is obvious to many people. It is less common to see artists that are also scientists or vice versa. Even if we have a bias toward one of those fields, we should not forget to neglect the other one. There are many insights to be gained by being both artist and scientist. But first, let’s examine the value of each on its own.

After escaping slavery, Frederick Douglass was looking for ways to assist in his fight for civil rights and anti-slavery. “He who speaks to the feelings, who enters the soul’s deepest meditations, holding the mirror up to nature,” Frederick Douglass wrote, “will be sure of an audience.”

In his speech “Pictures and Progress,” he declared how artists can use photography as an effective method of changing people’s perception. “The few think, the many feels,” he pointed out, “the few comprehend a principle, the many require an illustration.” Douglass loved photography and regarded it as an opportunity to redefine the public perception of what it meant to be an African-American. As a mirror of reality, photography became a weapon in his fight.

He wrote essays on the topic and sat down for a portrait at art studios whenever he had a chance. He loved studying photography, both in theory and how it could be used as a public relations weapon combating stereotypes and prejudices against African Americans.

While most know Frederick Douglass for his escape from slavery and as a political activist and reformer, through photography as an artist, he changed our perception of African-Americans. As a champion of photography, he sat for more photographs than even President Abraham Lincoln. He expanded our visual vocabulary by using photography as a technology for communication rather than a form of art.

Art is a state of being, according to Robert Henri. As he defined it in The Art Spirit, “Art is simply a result of expression during right feeling. It’s a result of a grip on the fundamentals of nature, the spirit of life, the constructive force, the secret of growth, a real understanding of the relative importance of things, order, balance. Any material will do. After all, the object is not to make art, but to be in the wonderful state which makes art inevitable.”

Art pushes the envelope. According to inventor Ray Kurzweil, the world of art is ahead of the world of science in appreciating the power of human perception. Or as Leonardo da Vinci put it, art is the queen of all sciences communicating knowledge to all the generations of the world.

Of course we also need to study the sciences. Cherishing both arts and sciences provides us with a fuller understanding. Nature is one of life’s greatest teachers. There are so many secrets in nature that we have yet to be discovered.

Four years after entering Cambridge University in 1661, a young Isaac Newton had to return to his childhood home due to an outbreak of the bubonic plague. One day, while sitting in the orchard, he observed how an apple fell off the tree. It piqued his curiosity why apples fall straight to the ground.

Archimedes, after taking a bath, allegedly discovered the principles of buoyancy through a similar form of serendipity. Upon his discovery, he ran outside naked through the streets of Syracuse, shouting “Eureka!” How much truth is in either of these stories is less important. What matters is the impact of a scientific mind when it’s applied in nature.

In one of my first interviews for Pensive, a podcast that engages thinkers and doers philosophically, I spoke with Doug Carmichael, a former Harvard fellow, and learned about the importance of understanding science and nature.

“Why is the sky blue? Most people of your age don’t know the answer,” he told me. “I will sometimes talk to a group of technical people, and tell them ‘You have never designed anything as complicated as a blade of grass.’ A blade of grass can reproduce. It can handle different seasons. It can be stepped on. Try it.’”

We conduct our lives through reasoning by analogy. Analogical thinking is easier than thinking by first principles. We say something is impossible because it wasn’t possible in the past. Instead, we need to reason by first principles. It is the physicist’s way of reasoning.

“First principle’s thinking is a physicists way of looking at the world,” explained Elon Musk in an interview with entrepreneur Kevin Rose. “You boil things down to the most fundamental truths and then reason up from there.” It sounds easy, but it is hard to implement because we are so wired to reason by analogy.

A scientific mind can help you debunk old assumptions that no longer serve you. The rational mind often contains a healthy dose of skepticism. You gather facts and test them by experimentation.

Christopher Columbus is an example of combining both arts and sciences. Columbus belonged to an artisan family, but his heart belonged to that of an adventurer. When he grew up, he craved to venture out into the sea. It was a feeling he would never lose. He learned the ropes of a sailor and educated himself on everything that was important. After the Ottoman Empire cut off the land routes to India, European traders were looking for new ways to access lucrative spices. Columbus recognized the opportunity and trusted his intuition as a sailor and explorer.

He pleaded with neighboring countries to finance his venture. They all rejected him at first. After appealing to Queen Isabella’s religious spirit, she agreed to partially finance his venture. After securing additional funding by investors from Seville and Valencia, Columbus began building three ships — the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. He recruited able men and set sail in August of 1492, in search for a westward route to India.

It was a long journey, and he never found what he was looking for, but he discovered something even more satisfying — an entirely new continent. While he wasn’t the first man to set foot on America, his discovery created a bridge between the Americas and Europe. Despite being met with rejections, uncertainty, and imperfect knowledge, Columbus combined his skills as a sailor and trusted his intuition that there was more to be found.

By having both arts and sciences as our companion, we unlock different mental models by using both the rational and the intuitive mind. Some of the best scientists were also artists, while some of the best artists were also scientists. If we can think like an artist and a scientist, we can look at the world as only few people do.